Saint Andrews is a unique town, recognized internationally for its collection of preserved historic architecture spanning more than 240 years. However, the town’s history is much older. While most come to see the architecture and landscapes still standing since the arrival of the Loyalists in 1783, the traditional territory of the Peskotomuhkati Nation is the watershed of the Schoodic (St. Croix) River and Passamaquoddy Bay.

The Passamaquoddy Tribe called the current Saint Andrews location ‘Qua-nos-cumcook’. Later ‘legend’ has it that a priest from a passing French ship erected the cross of Saint André on the shore, thereby sowing the seeds for the present name. As New France expanded throughout North America in the 17th century, settlements came and went, but French explorers and traders did set foot at Campobello and Deer Island and at Dochet’s Island in the St. Croix River Estuary.

These included Samuel de Champlain in 1604 when he and his sailors first experienced the beauty of the region, but also witnessed the hardships of settling on the land. After moving on to Port Royale in 1605, the French often returned to the St. Croix River to establish trading contacts with the Passamaquoddy who would migrate annually to the protected shores at Qua-nos-cumcook to fish and dig clams.

The onset of the American Revolution led to both challenges and opportunities for the forefathers of Saint Andrews. In October, 1783, a group of United Empire Loyalists arrived to settle what was to be known as Saint Andrews. Having left their homes in New York and Massachusetts, they initially journeyed to become pioneering families to an area now known as Castine in Maine, where they could remain loyal to British values and set up the locally responsible government in the British parliamentary tradition. However, on learning that the new international boundary was to be at the St. Croix River, they renewed their determination and with their families, towed their recently built homes to Saint Andrews.

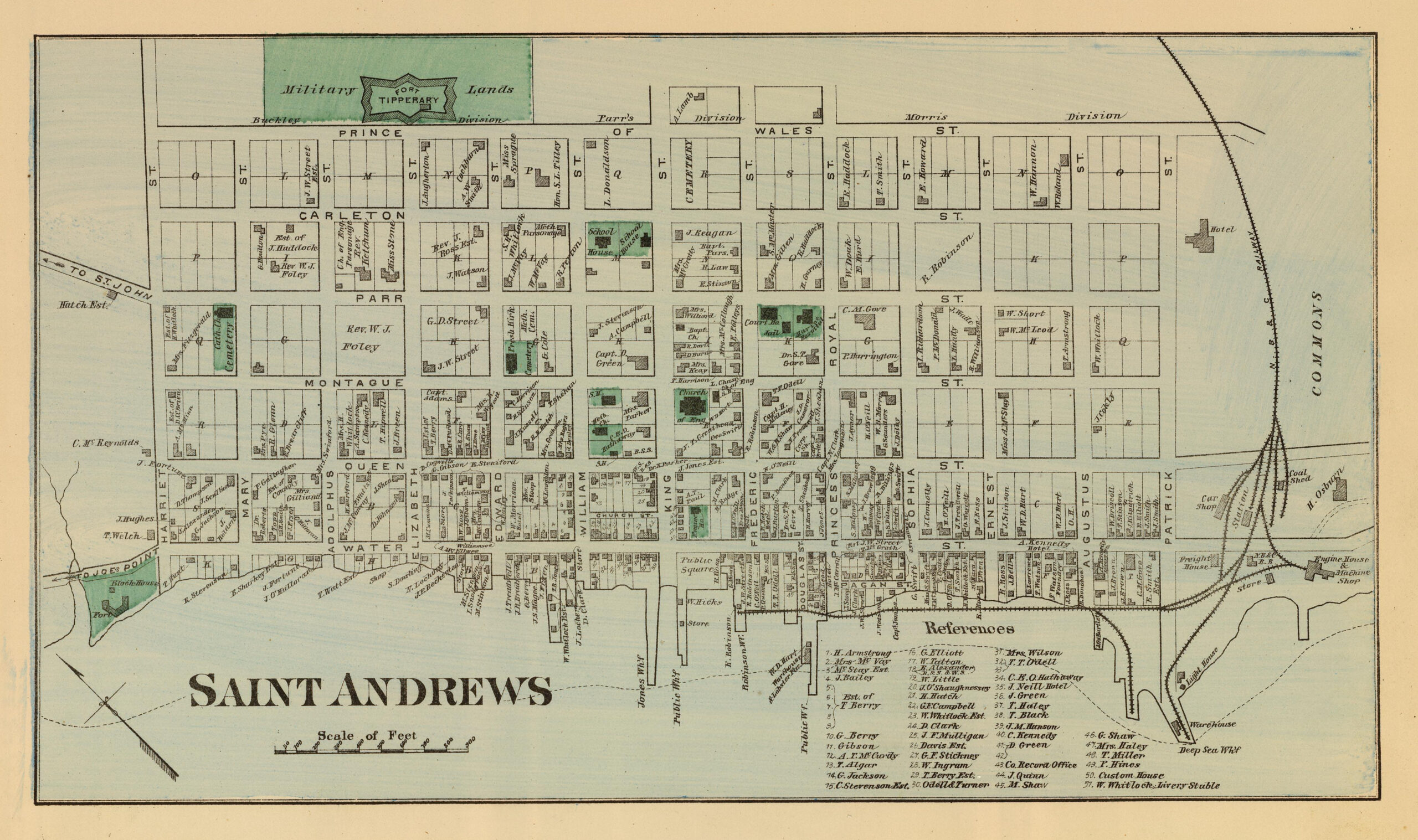

While many pioneering towns have a central core, radiating outward in an irregular manner, Saint Andrews, like many British Military sponsored settlements of the time, was to be laid out in a grid manner. Sixty square blocks were created, bounded by streets named after members of the British Royal Family. Other irregular blocks were established along the harbour front (now Water Street) that served to support the growth of economic activity as Saint Andrews grew to be a major sea-port in the 19th century. Within five years, 600 buildings were built and 3,000 people had made it their home.

Within time nearby Saint John grew and prospered, while Saint Andrews entered a period of economic decline.

By 1911, only 1,000 citizens remained. However, Saint Andrews did not fade away. Blessed with quiet beauty, it became a summer-time destination of many well-to-do Americans and Canadians. Free of ragweed and near the sea, the area led Sir William Van Horne, builder of the Canadian Pacific Railway and its President, Lord Shaughnessy, to cultivate Saint Andrews as a resort destination. In turn, summer ‘cottages’ were built and a style of summer life sprung up around the Algonquin Hotel. To advertise its natural setting, the Railway promoted the destination as Saint Andrews-by-the-Sea. Since the 1920s, the population of Saint Andrews has remained stable, and with its friendly character and natural beauty, summer visitors have come to enjoy its streetscapes and shops every summer.

In 1995, the original Town Plat of Saint Andrews was designated a National Historic Site for its design and the collection of architectural styles present within. Styles range from simple Saltbox and Cape Cod structures to elegant Georgian town houses and summer homes built in the American “shingle” style. Many of the latter were designed by Edward Maxwell, the renowned Montreal architect. The junction of Montague and King Streets, graced by an elegant Anglican church and townhouses in Georgian and Federal styles, has been described as the finest street intersection in Canada. Many of the commercial buildings on Water Street also date from the late 18th or early 19th century and, where gable ends face the street, they create roof lines reminiscent of the older parts of Bergen in Norway or Bristol in the United Kingdom.

Since being named a National Historic District, the majority of Saint Andrews has had no protections for its heritage structures. While the secondary municipal plan, introduced in 2020, helped to protect the Water Street Commercial Business District, there has been nothing in place to protect residential heritage structures from being demolished.